Brazil is a massive and fascinating country, with enough adventure to keep you exploring for a lifetime. We’ve had the privilege to travel all over Brazil over the course of our 2 trips to the country in 2014 and 2016 and had some incredible experiences there.

*This post may contain affiliate links, as a result, we may receive a small commission (at no extra cost to you) on any bookings/purchases you make through the links in this post. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Read our full disclosure

Although traveling in Brazil might not always be easy, it is more than worth it!

Here is our list of the most amazing places to visit in Brazil.

The Best Places to Visit and Things To Do In Brazil

Iguaçu Falls

Iguaçu Falls is one of the most significant Brazil landmarks and, in our opinion, the most spectacular waterfall in the world. Spanning nearly 3 km (1.86 miles), this massive cascade demands a place on your list of what to do in Brazil.

Traveling Soon? Here is a list of our favourite travel providers and accessories to help get you ready for your upcoming trip!

While you’re there, you can hike some of the extensive trail network surrounding the falls. If you don’t mind getting wet, hop in a rubber boat and get up close and personal to the base of the waterfall. You can visit Iguaçu from both the Brazilian and Argentinian sides.

Read More: Tips for Visiting Iguazu Falls in Brazil and Argentina

Pantanal

If you’re a nature lover and want to dive deep into Brazil’s wetlands, Pantanal should be high on your list. Located primarily inside the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Pantanal is the largest continuous wetland on Earth. There’s no shortage of flora and fauna here, including capybaras, parrots, jaguars, and the signature giant lily pads.

The Pantanal is also famous for having the largest crocodile population in the world. Take a boat cruise through the wetlands with a local guide to get up close and personal with some of these amazing animals. Of all the natural places in Brazil, this is one of the best.

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro is the most famous city in Brazil for good reason. Rio has some fantastic nightlife, culture, and food, and you’ll never run out of thing to do here.

Hike up the Christ the Redeemer, sip caipirinhas on Copacabana Beach, and get to know the real side of the city by visiting one of the favelas. If you want to spend even more time in nature, the city is full of gardens and parks such as Rio Botanical Gardens, Parque Lage, and the Tijuca National Park, all right inside the city.

You’ll also want to visit one of the most famous Brazil landmarks, Sugarloaf Mountain, and ride the cable car to the top for unrivalled views of the city. As one of the ultimate best places to visit in Brazil, Rio is one city that can’t be missed.

Paraty

Tucked in between Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, Paraty is a small, artsy town right on the coast. What used to be the center of the Brazilian gold rush is now one of the up and coming Brazil tourist attractions.

Nature really steals the show here – you’ll find endless beaches, mountains, jungles, and waterfalls all right nearby. In particular, don’t miss the Saco do Mamanguá, Praia Grande, and a visit to the Jabaquara Mangroves. The old town boasts a historic colonial style and vibrant pastel colours.

Paraty might be one of the more under the radar places to visit in Brazil, but it definitely deserves a spot on your itinerary. We loved it here!

Curitiba

Curitiba is another city often overlooked by travelers in Brazil, but we think you shouldn’t count it out.

It is one of South America’s most sustainable cities and leads by example with its excellent transportation system and environmental efforts. The city is full of green spaces like Parque Barigü, and the cityscape can best be seen from the top of the Torre Panorâmica (Panoramic Tower.)

Brasilia

Brasilia is really a funky city with lots of modern architecture and symmetry to add to the new-age feeling. The whole city is roughly shaped like an airplane, with two main streets holding the places of the wings. The Cathedral of Brasilia is a big highlight, with its abstract design commanding the attention of all who pass by.

In fact, almost everything in Brasilia’s main area feels modern, from the city’s bridges to the public transportation system to Alvorada Palace, the house of the Brazilian President. We felt like Brasilia was a utopian city, designed to create a perfect place to live and work.

Read More: Behind the Facade of a Utopian City of Brasilia

Amazonia National Park

Amazônia is a massive national park in the state of Pará, Brazil. This destination is quite remote, but worth it if you want to experience some of the hidden secrets of the Amazon Rainforest.

To visit, you’ll start in the city of Itaituba where you’ll likely want to hire a guide. If you decide to go on your own, make sure to get a vehicle with four-wheel drive as a lot of the roads are unpaved.

Once in the park, you’ll have the opportunity to cruise along the river or trek through the jungle to spot monkeys and countless species of birds. Since deforestation is sadly all too common in the rainforest, visiting Amazônia sustainably is one of the best things to do in Brazil without a doubt.

Recife

This industrial city in Northeast Brazil is often overlooked by travelers. Although Recife might have a rough exterior, the beach is really something special. Directly adjacent to modern high rises, it offers an opportunity to relax in the sun and swim over the reefs at Boa Viagem Beach.

The colourful old town also warrants a visit to see elegant architecture and vibrant markets. In addition, don’t miss a visit to Casa da Cultura for some traditional dance performances and exhibits, as well as the Instituto Ricardo Brennand to see a historic castle by the sea.

Ouro Preto

Tucked into the mountains about an hour and a half south of Belo Horizonte, Ouro Preto is a small town full of rustic beauty. Located in the southern part of the state of Minas Gerais, Ouro Preto is surrounded by lush jungles and green hills.

“Minas” literally means “mines,” so if you want to experience some of the region’s most interesting features, venture out of town to the Minas de Passagem, a gold mine constructed in 1719. Next, head to the Parque Estadual do Itacolomi for some peaceful hiking trails and nature walks.

A word of caution here – the streets are quite steep and walking around the city is a workout in itself!

Salvador

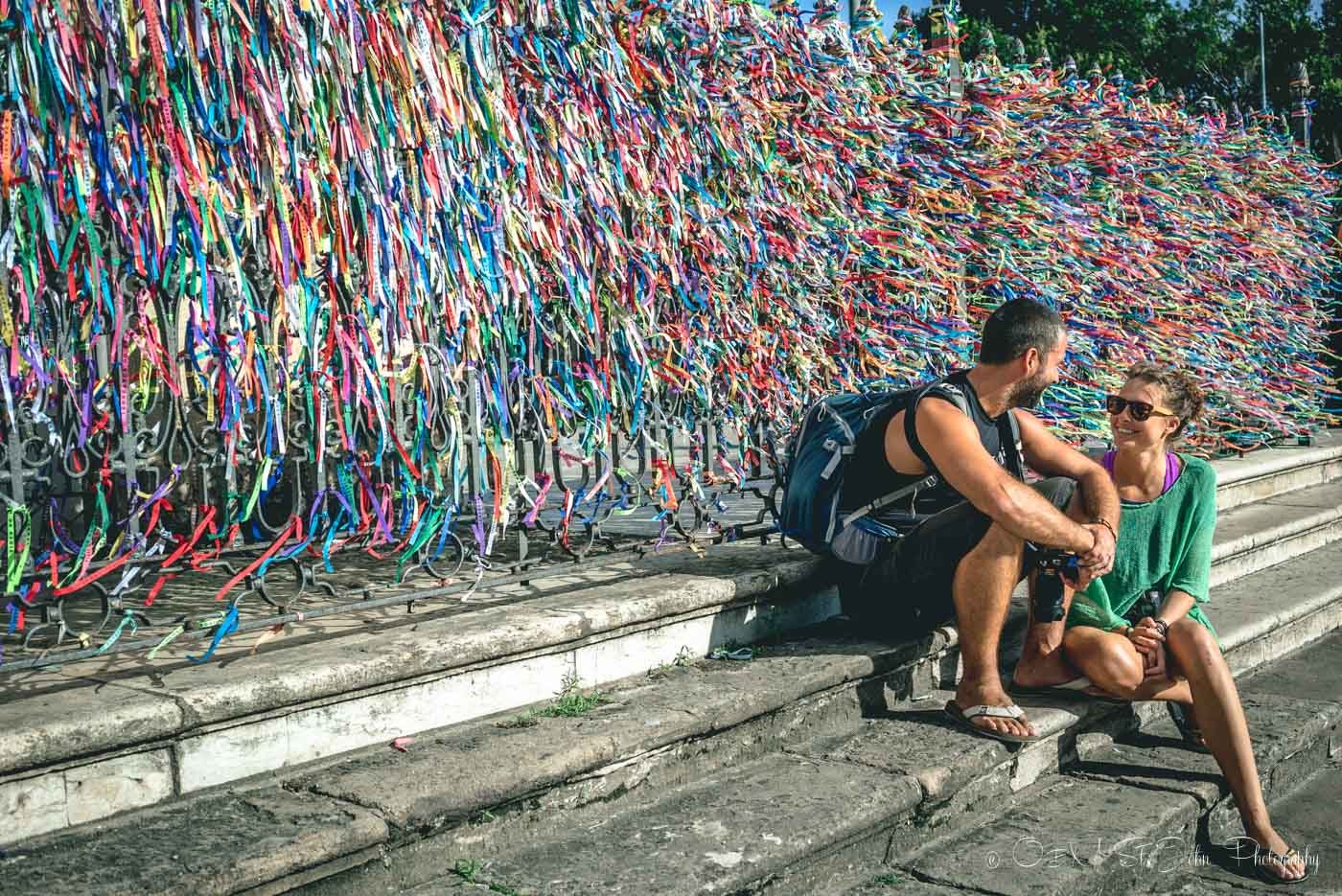

The city of Salvador is one of northeast Brazil’s greatest treasures. The city is a charming and relaxed seaside paradise that has seemingly endless cobblestone streets for you to explore.

Salvador is a vibrant mix of cultures, with a mix of Africa, European, and indigenous influences. The city is also with brimming with history. You’ll find evidence of the slave trade that was once so prominent here and over 300 churches within the city borders.

If you’re looking for the best sunset spot in town, make sure to visit the Santo Antônio da Barra Fort at dusk.

Fernando de Noronha

Visiting Fernando de Noronha, one of the most unique places in Brazil, was a very special experience. The islands are still quite an under-the-radar destination and will remain protected from over-tourism through the limit of only 400 tourists per day.

The entire island chain is a UNESCO protected area and is practically heaven on Earth for the eco-conscious traveler. You can hike across the 21 different islands, and swim or dive in the protected marine park. The beaches here are secluded, pristine, and sometimes require a hike to get to, making them all the more rewarding to have all to yourself.

Although the islands of Fernando de Noronha are quite expensive and out of the way, you’ll have paradise all to yourself if you’re willing to make the journey.

Read More: Fernando de Noronha – Visiting Brazil’s Exclusive Eco Paradise Island

Jericoacoara

Although the small town of Jericoacoara is primarily known for fishing, it’s earned a spot on the tourist trail for the incredible Jericoacoara Beach. The beach is located inside of Jericoacoara National Park, an otherworldly landscape of rolling white sand dunes.

While in town, you’ll have the opportunity to try a number of adventurous activities, kite surfing being the most popular one. Although quite remote, Jericoacoara has a fantastic atmosphere. The small town has lots of eclectic stores, nightlife spots, and great restaurants that make it easy to not want to leave.

Lençóis Maranhenses

If you haven’t had your fill of white sand dunes, make sure to visit Lençóis Maranhenses National Park. The park is full of pearly, undulated mounds that stretch out for miles in every direction.

Nestled in the valleys between them are emerald green freshwater pools. The entire area is a protected wildlife zone and has tons of salt marshes and private lagoons too. The terrain is one of the most unique things to see in Brazil – from above, it truly looks like another planet.

Read Next: 7 Destinations You Have to Visit in Northeast Brazil

BONUS: Amazing Cultural Experiences in Brazil

Carnaval

If you want a true taste of culture and wild spirit, attending Carnaval is one of the most exciting things to do in Brazil. The festival takes place at the beginning of Lent, the 40 day period before the celebration of Easter. The massive street parties go on for an entire week and feature giant parades with massive floats, each one representing a different samba school competing in the competition.

Although Rio’s Carnaval is the largest and most famous, you can experience other Carnaval parties all around Brazil in cities like Vitória, São Paulo, Salvador, and Belo Horizonte. This is as much a Brazil tourist attraction as it is a celebration of Brazilian art and culture.

Expect rambunctious music, scantily clad dancers, flowing drinks, and lots and lots of fun!

Football Match

Brazilians go crazy about soccer and going to a game is one of the most exciting things to do in Brazil. We had the chance to attend the World Cup back in 2014 and it was an unforgettable experience.

During your trip to Brazil, you’ll likely have many opportunities to attend a match, so don’t hesitate to grab yourself a ticket to a local match. Once inside the stadium, you’ll be in the midst of a full blown party atmosphere. Flags will wave, drums will beat, and people will be screaming their heads off. Make sure to dress up in the colours of your favourite team and join in the fun!

There is certainly no shortage of awesome adventures and inspiring places to visit in Brazil. On our journey around the country, we encountered inspiring nature, pulsating cities, and fascinating culture. Although there are countless things to see in Brazil that are worth your time, we hope this list got your started with some of the country’s most exciting highlights.